TMG Group LLC

1441 Kapiolani Blvd Suite 1114

PMB 411671

Honolulu, HI 96814-4406

Over the past several years, I have examined thousands of Catholic church death records on the Family Search website. Each time I return, I'm continually amazed by the short lifespans people endured during Mexico's colonial period and the various causes of death. Diseases like smallpox, typhoid fever, measles, and later tuberculosis swept through in waves, decimating populations. Conflicts between the Spaniards and indigenous peoples also claimed many lives. Numerous other challenges were part of daily life in northern Mexico's deserts. Although many deaths remain mysterious to us today, we now have a better understanding of the likely causes, which were mostly unknown at the time. Interestingly, older church records often listed symptoms as causes of death, if any cause was mentioned at all. It was common to see entries like "murio de fiebre" (died of fever) or "murio de dolor de costado" (died of pain in the side), indicating symptoms of larger, unidentified illnesses. I've also encountered many instances of "murio de viejo" (died of old age) for individuals in their 50s, which isn't very old by today's standards! Alongside these common descriptions, I've found notable entries such as "murio a los manos de los enimigos Comanches" (died at the hands of the enemy Comanches) and "murio de un golpe de caballo" (died by a horse's kick, likely to the head), offering insight into the daily dangers of that era.

What happened to the bodies of those who passed away? Was there a church service held? Where were they buried? Beyond my grandparents, I am unsure of the burial locations for most of my earlier ancestors, and I may never find out. This is partly because it is only in more recent generations that details of death and burial have been recorded more consistently, extensively, and in an organized fashion. Nowadays, tombstones usually include some of this information and civil records are kept to document much of the relevant details.

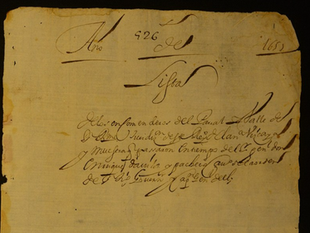

Following the Spanish conquest in the early 1500s, the Spanish introduced the funerary customs of European churches, particularly the Catholic Church. When someone died, a service was held at the church, and the nature of the service typically depended on the family's financial "contribution" to the church. Many records include the terms "cruz alta" or "cruz baja." The former usually signified a wealthier family capable of making a significant contribution to the church, resulting in a more elaborate and personalized service. The latter was for those who could contribute some money thus, receiving a basic funeral service. Additionally, the term "de limosna" referred to the type of service provided to the poorest individuals who could not make any financial contribution and therefore, received the most basic service.

Burials often reflected an individual's wealth and social status. The most desirable burial sites were in and around the church, typically reserved for society's elite. These locations were highly sought after due to their perceived sanctity, believed to keep the deceased's soul closely connected to the church. Additionally, being buried there served as a status symbol. NOTE: Interestingly, the first two records from above state that the bodies were buried "vajo del coro," meaning "under the choir," possibly referring to a music section of the church or another specific area within the church. In 1798, the Spanish king ordered changes to burial locations, largely discontinuing burials at or near churches, with few exceptions**. Today, we understand that churches of that era were often centers for disease transmission and poor sanitation, worsening health issues. Besides those who were able to have a church service, many others passed away without receiving such services. My great-grandfather, Benigno Quintela, was killed during the Mexican Revolution fighting for Pancho Villa in December 1916. Newspaper reports indicate he died in a firefight about 70 miles south of Presidio at a place called Polcerios Ranch. I have been unable to locate this ranch, but I suspect his comrades probably dug a hole and buried him there, marking the spot with a wooden cross made of sticks. This practice was likely more common than we would like to think due to the nature of war, the harsh environment and the transient lifestyle of many searching for new opportunities across the sparse deserts of northern Mexico.

If you would like to read more about some of the funerary practices in this part of the world, please see the source list below which is a very good read and also contains a comprehensive listing of the cemeteries in the Big Bend of Texas as well as the names of many that were buried there.

Source:

** "Cemeteries and Funerary Practices in the Big Bend of Texas, 1850 to Present, by Glenn P Willeford, and Gerald G. Raun, pg. 27"